One could spend

weeks visiting the churches of Paris. But on previous trips, I was

happy to visit only Notre Dame. I’m not interested in the churches in the same

way some visitors to France are. I can

appreciate their beauty, but it’s always a challenge for me to know that the

stones of the churches were delivered on the backs (literally and figuratively)

of the poor.

Even so, churches

are at the center of medieval life, and there are a number of churches in Paris

where Christine might have worshiped. We

know that she spent time in a small Queen’s Chapel at St. Pol because she

writes about the interior decoration with wonder and affection. On this trip, I wanted to go into the major

churches of her time to see what she might have seen.

|

This Mary of Egypt statue was installed in the 13th

century, so it has stood on the church portal since

before Christine was born.

|

I explored a

number of churches, and the iconography and stained glass in each was

impressive, but walking up to St. Germain L’Auxerrois I got a sense that

something about the church was different.

Most churches have Mary somewhere on the portal, but this church had a

number of female saints, on some portals there were more female saints than

male ones.

Particularly

intriguing was the sculpture of a woman who didn’t seem to be wearing any

clothes. Her body was covered by her

sculpted hair. She held a small drape and seemed to be carrying three big stones

or loaves of bread. I’m not Catholic,

but I’ve been interested in the Middle Ages for a long time, so I’m familiar

with many saints. This one I did not

know. I was sharing a flat with my

friends, both of who are Catholic, but when I asked them later, neither of them

were familiar with a naked female saint.

Inside, the images

of women continued. Several windows in, I found another naked woman covered

only by her hair—no drape, no rounded objects--just hair through which there

was a titillating bit of skin around her belly button.

It didn’t take much

research to discover that both of the women were named Mary. Both were reputed

to be prostitutes before their conversions. It was a regular medieval practice

to depict fallen women without their hair, so you may have already guessed that

one of these women, the one in stained glass inside, is Mary Magdalene.

The other saint

is Mary of Egypt, a prostitute who converted and spent 40 years of penance

alone in the desert. She took only three

loaves of bread with her. The only contact with people she had was with a

priest before her death who gave her the host and consecrated her burial a year

later.

|

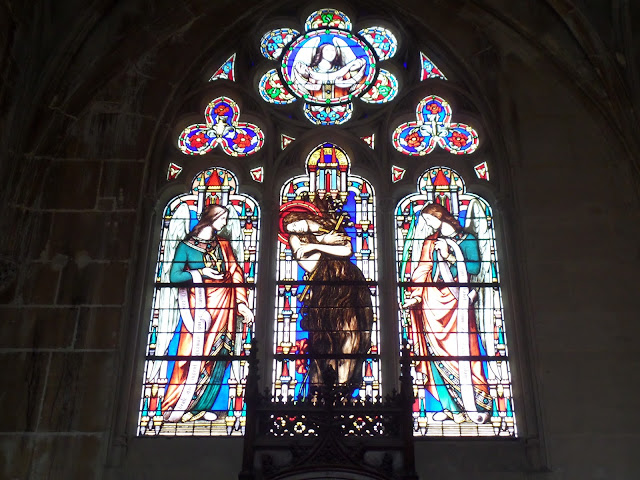

| Another Mary of Egypt statue, the background resembles St. Chappelle, but I'm not sure where I took this picture. Anyone know? |

If Christine

visited this church, she might have been reminded of, as I was, the particularly

conflicted role of women in church culture.

There are many female saints, many depicted in honor on the portals and

windows of churches, yet it was a common practice for learned church men to complain, quite loudly, about women’s more sinful natures.

In her argument

about The Romance of the Rose and

eventually in her City of Ladies and

the Treasure of the City of Ladies,

Christine brings worthy female models to our attention as an argument against

the widespread disregard for women.

Indeed, she mentions both Mary Magdalene and Mary of Egypt in her Treasure of the City of Ladies.

Visiting

churches allowed me to read the texts of Christine’s day. The statues and windows aren’t just ornaments

on a medieval church, they are the Bible come to life, the lessons and stories

that are intended to guide the lives of God’s people, most of whom would not be encouraged to read the Bible even if they could.

The church still

maintained strict access to interpretation in the Middle Ages, and with windows and statues they could highlight the stories and values they wanted

parishioners to attend to. These

values and stories could be set by the powerful abbotts and clerics who worked

with the stone masons and architects to design not just the churches but also

their ornamentation.

No comments:

Post a Comment